Hyperborea to the Indians

“Indeed, the inhabitants of the White Land worship only one God.” - Mahabharata Santi Parva

In the realm of Hinduism, we find an incredible amount of ancient literature, some of which dates back to 2,000 BC; the oldest of this literature being found in what are known as the ‘Vedas.’ That being said, at this point we might turn our attention to what is known as the ‘Mahabharata,’ which is said to have been compiled in the 3rd century BC, although modern academics believe that the contents of the ‘Mahabharata’ must have existed as oral tradition for quite some time before first being written down. The ‘Mahabharata’ is the world’s longest poem ever written, consisting of over 200,000 verse lines, divided amongst 18 chapters, which are called ‘Parvas.’ Of interest to us is the ‘Shanti Parva,’ the longest of the Parvas, as it speaks of a land called ‘Sweta Dwipa,’ which translates to “white island,” “white land,” or “white continent.”

It is said that Sweta Dwipa is situated at the base of Meru Mountain, far to the north of the Himalayan Mountain range, and adjacent to the “Ocean of Milk.” The ‘Shanti Parva’ describes Sweta Dwipa as being solely inhabited by only the most loyal devotees and worshipers of Narayana, the Hindu god of creation. Interestingly, these inhabitants of Sweta Dwipa are said to be completely white in complexion, rich in knowledge, and without sin:

“On the northern shores of the Ocean of Milk there is a magnificent land called Sweta Dwipa, White Land. The complexions of the men that inhabit that land are as white as the rays of the moon and they are devoted to Narayana.”

“Worshipers of that foremost of all beings, they are devoted to him with all their souls. They all enter that eternal and illustrious deity of a thousand rays.

“Indeed, the inhabitants of the White Land worship only one God.”

“All of them were white like the moon with every mark of auspiciousness. Their hands were always joined in prayer.”

“The effulgence emitted by each of those men resembled the splendors that Surya [ancient Hindu sun god; divine solarity] assumes.”

“Indeed, we thought that that land was the home of all light. All the inhabitants were equal in energy. There was no superiority or inferiority amongst them.”

“As we stood among those thousands of men, all of purest descent, no one honoured us with a glance or nod. Those ascetics, joyful and pious … did not show any kind of feeling for us.”

“At that moment, a divine Being spoke to us from the sky, saying, ‘These white men, who are without their outer senses, have the capacity to behold Narayana.’”

“Incapable of being seen because of his dazzling radiance, that illustrious deity can be beheld only by men who, in the course of long ages, succeed in devoting themselves only and absolutely to him.”

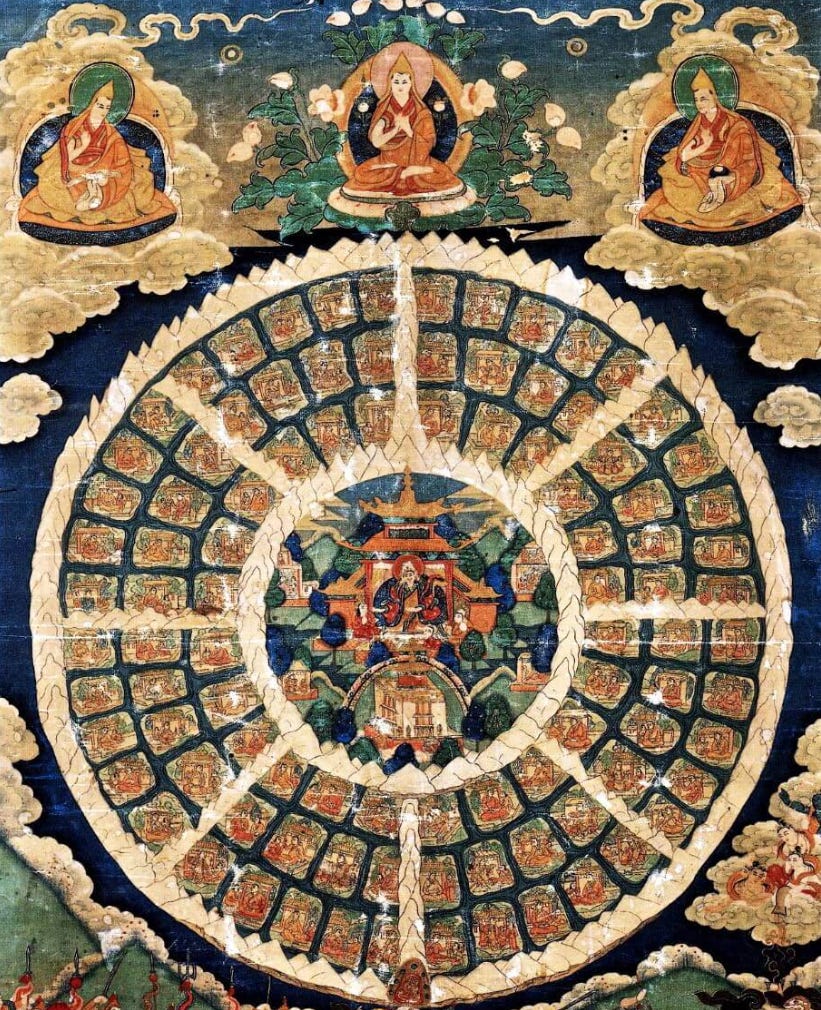

Curiously, this description of Sweta Dwipa, full of white-skinned people who worship a monotheistic, radiant solar god of creation, is very similar to the description of Shambhala, the legendary northern land of the spiritually ascended, which was first cataloged in the 11th century A.D. Hindu text, the ‘Kalachakra Tantra’ [Wheel of Time].

This text introduces King Manjusrikirti, who is said to have ascended to the throne of Shambhala, becoming king of this wonderful northern land of spiritual purity. It is said that King Manjusrikirti ruled over 300,150 Shambhalans, many of whom religiously worshiped the sun as their god. After ascending to the throne, King Manjusrikirti, whom had adopted Kalachakra Buddhism, gave an ultimatum to these Shambhalan solar worshipers: abandon your solar worship and convert to Kalachakra Buddhism or be banished from Shambhala. As such, there was a mass exodus from Shambhala, these solar worshipers being exiled from their northern homeland in which they had lived for ages. The implication of this Shambhalan history is that it existed, originally, as a predominantly solar worshiping society, with the solar worshipers ultimately being exiled from their own kingdom.

Regarding Shambhala’s geographic location, we might reference the ancient Tibetan Buddhist text called the ‘Tengyur,’ within which is a guidebook to Shambhala, called the ‘Kalapar Jugpa.’ This guidebook was first translated from Sanskrit into English in 1,604 AD by a prominent Tibetan Lama and historian named Taranatha, who had discovered it buried in the archive of a Tibetan monastery. Interestingly, for numerous stylistic and content substance reasons, it is thought that the text of the ‘Kalapar Jugpa’ dates back to the 10th century AD, around the time that Kalachakra teachings first began to manifest in India. The ‘Kalapar Jugpa’ is framed as a dialogue between a great sage named Arya Amoghankusha who is speaking to a group of lesser-sages as they search for wisdom that might save them from spiritual degeneracy. During this dialogue, Shambhala’s capital city and spiritual center, Kalapa, is introduced:

“Those who wish to go to Kalapa without returning, in search of the great meaning, can go and obtain what they seek from the Master and sages of Shambhala.”

Subsequently, a detailed series of geographic instructions are given, with which one might make the long and arduous journey to far-off kingdom of Shambhala:

“Take a boat to the shores of western India. Many countries lie north of there, but they will not be enjoyed: If the seeker ventures into them, he will lose himself in aimless wandering. Avoiding the wrong direction, he should go northeast. Then, going north to north, he will travel for six months past numerous cities until he reaches a great river named Satru…”

“Beyond them, on the far side of the river he has just crossed, lie the cities of northern Jambudvipa [the known world]. The people of these places are happy and prosperous and live without fear or sadness.”

“Go on, across China, Great China, and the northern lands, always going north. He who has the power of mantras will not take more than six months to cross all the countries of these vast and far-off regions.”“After going north for several hundred miles, he will reach a valley called Samsukha… From there he will go on through the Forest of Perpetual Happiness. And passing beyond that, he will come at last to the great city of Kalapa and enter the presence of the King of Shambhala.”

Very curiously, over forty years prior to Taranatha finding and translating the ‘Kalapar Jugpa,’ another series of travel instructions to Shambhala were given by Ngawang Namgyal, who was the prince of Tibet at the time, in his 1,557 AD missive ‘The Knowledge-Bearing Messenger,’ which he wrote so that one of his royal couriers could deliver a message to Shambhala on his behalf. It is the writings of Ngawang Namgyal that we find a very similar set of instructions leading to Shambhala:

“But the power and teachings of the sages will ward off these threats to your life and permit you to follow the path that leads to the north, toward Shambhala. After many harrowing days of travel, you will come out in a beautiful land of gold and jewels–the country of fabulous beings who are neither men nor gods … The fabulous maidens who dwell there, always happy and singing songs, have lovely moon faces, beautiful as lotus blossoms, with eyes like blue flowers. Sashes of fine cloth decorated with pearls adorn their golden bodies.”

“A few miles north rises another peak, called Incense Mountain. From a distance its green meadows and lush foliage make it look like a heap of luminous emeralds. Medicinal herbs and incense trees grow all over its gentle slopes, filling the air with a delightful scent. Numerous sages, powerful yogis, live on the mountain in jewel-like caves. They sit erect in constant meditation, gazing straight ahead with never a flicker of their deep blue eyes. Their skin is gold and a slight smile graces their lips. As soon as you see them, prostrate yourself in homage and give them offerings of beautiful flowers. Then ask for their aid and advice in reaching Shambhala.”

“After crossing the mountains, you will have to go through one last forest filled with snakes and wild animals, but if you show friendliness and compassion to whatever creatures you meet, you will have no trouble. Although you feel exhausted and sick from the rigors of the journey, hold onto your aim and continue to dedicate your efforts to the benefit of all things. Then you will see, at last, the cities of Shambhala, gleaming among ranges of snow mountains like stars on the waves of the Ocean of Milk.”

From these accounts, one thing can be certain: the ancient Hindu theologists viewed the north not just as a metaphysical realm of spiritual purity, but also as a real, geographic location that could be physically traveled to if one was sufficiently motivated to carry out the long, difficult journey. Additionally, worth noting, the geographic route to Shambhala was painstakingly documented and preserved over centuries, making it difficult to imagine that a set of travel instructions as detailed as this would be maintained for hundreds of years for a location that didn’t actually exist.