The Greco-Roman Hyperborean Concept

“Nevertheless, it seems to be true that the extreme regions of the earth, which surround and shut up within themselves all other countries, produce the things which are the rarest, and which men reckon the most beautiful.” - Herodotus

The ancient Greeks and Romans wrote of Hyperborea for over 1,000 years, beginning in the 8th century BC when very little was known about the world. Over time, as Greek and Roman explorers gathered more information about what existed beyond their immediate geographic scope, the information pertaining to Hyperborea were progressively fleshed to such a degree that many later writers considered the existence of Hyperborea to be a concrete fact that wasn’t up for debate. To catalog the advancement of the Hyperborean concept amongst the ancient Greeks and Romans, below, we will go through a chronological series of Hyperborean sources in a way that is aimed at showcasing how the Hyperborean concept blossomed and grew as more information became available.

It is said by Herodotus, esteemed Greek historian of the 5th century BC, that two Greek writers before his time spoke of the Hyperboreans - Hesiod of the 7th century BC, and Homer of the 8th century BC:

“Hesiod however has spoken of Hyperboreans, and so also has Homer in the poem of the ‘Epigoni,’ at least if Homer was really the composer of that epic.”

Hesiod’s reference to Hyperborea is interesting because, due to discrepancies in writing styles, modern academics debate whether or not the ancient work in which it is found can rightfully be credited to Hesiod at all, or whether it must be credited to some anonymous contemporary of Hesiod. Regardless, what we know is that some ancient Greek author prior to Herodotus makes mention of the Hyperboreans in this way:

“the well-horsed Hyperboreans…”

Many of the writings we have from these ancient authors, who composed their literary works well over 2,000 years ago, are only preserved in fragments, with much of the original text having been lost to the ages. Nonetheless, this is our oldest direct reference to the Hyperboreans, dating back to the 7th century BC. Herodotus also mentions that Homer spoke of the Hyperboreans in his work called the ‘Epigoni,’ but expresses doubt over whether or not he is the original author. This comment is due to a 2,800 year long debate over whether or not a man named Antimachus, who was Homer’s 8th century BC contemporary, wrote the ‘Epigoni’ instead. As far as we are concerned, whether it was Homer or Antimachus that made this Hyperborean reference, we know that a Hyperborean reference was made nonetheless; although we don’t know specifically what was said. As such, this is technically the oldest known reference to Hyperborea; taking place in the 8th century BC. While speaking of Homer, we might note that certain components of the Hyperborean concept are repeatedly found in his other works, the ‘Iliad’ and the ‘Odyssey,’ although the specific word ‘Hyperborea’ isn’t used. Rather, he refers to Boreas, the north wind, on multiple occasions:

“As when the piercing blasts of Boreas blow,

And scatter o'er the fields the driving snow;

From dusky clouds the fleecy winter flies,

Whose dazzling lustre whitens all the skies.”

Homer also speaks of the people beyond Boreas, writing that during the battle of Troy, Zeus turned his gaze to the north, looking to the ‘Hippomolgi:’

“And where the far-famed Hippomolgian strays,

Renown'd for justice and for length of days;

Thrice happy race! That, innocent of blood,

From milk, innoxious, seek their simple food.”

Curiously, Hippomolgian directly translates to “people who drink the milk of female horses,” and may have been a very early pseudonym for the word “Hyperborean.” Worth noting, the word ‘Hyperborean’ being used to describe the people beyond the north wind in the ‘Epigoni,’ while Homer chose to use the word Hippomolgian in his ‘Iliad,’ might be one of the most compelling arguments that Antimachus is the true author of the ‘Epigoni’ rather than Homer.

Moving on from Homer, we might now speak of Aristeas, of the 7th century BC, author of the famous ‘Arimaspea,’ which, still to this day, serves as one of the most important sources of Hyperborean information, although, much to our misfortune, the contents of this ‘Arimaspea’ have almost entirely been lost or destroyed. That being said, we have the writings of multiple contemporary and subsequent Greek authors who read the ‘Arimaspea’ before it was lost, and it is from these writings that we gather much of what we know about Hyperborea in modern day.

It is written that Aristeas traveled for seven years in the lands to the northeast of Greece, detailing everything that he saw in his ‘Arimaspea,’ which ultimately became ancient Greece’s first piece of literature detailing what existed beyond their northern borders. Consequently, the ‘Arimaspea’ was incredibly popular and influential in ancient Greece, and served as a reference for countless subsequent Greek writers. It is from one of Aristeas’ 7th century BC contemporaries, Alcman, that we find our first primary source mention of the ‘Riphean Mountains;’ mountains that were most certainly discovered by Aristeas during his travels to Hyperborea, and which serve as a key geographic indicator regarding Hyperborea’s exact location:

“Riphean mountains, blossoming with forest, breast of black night.”

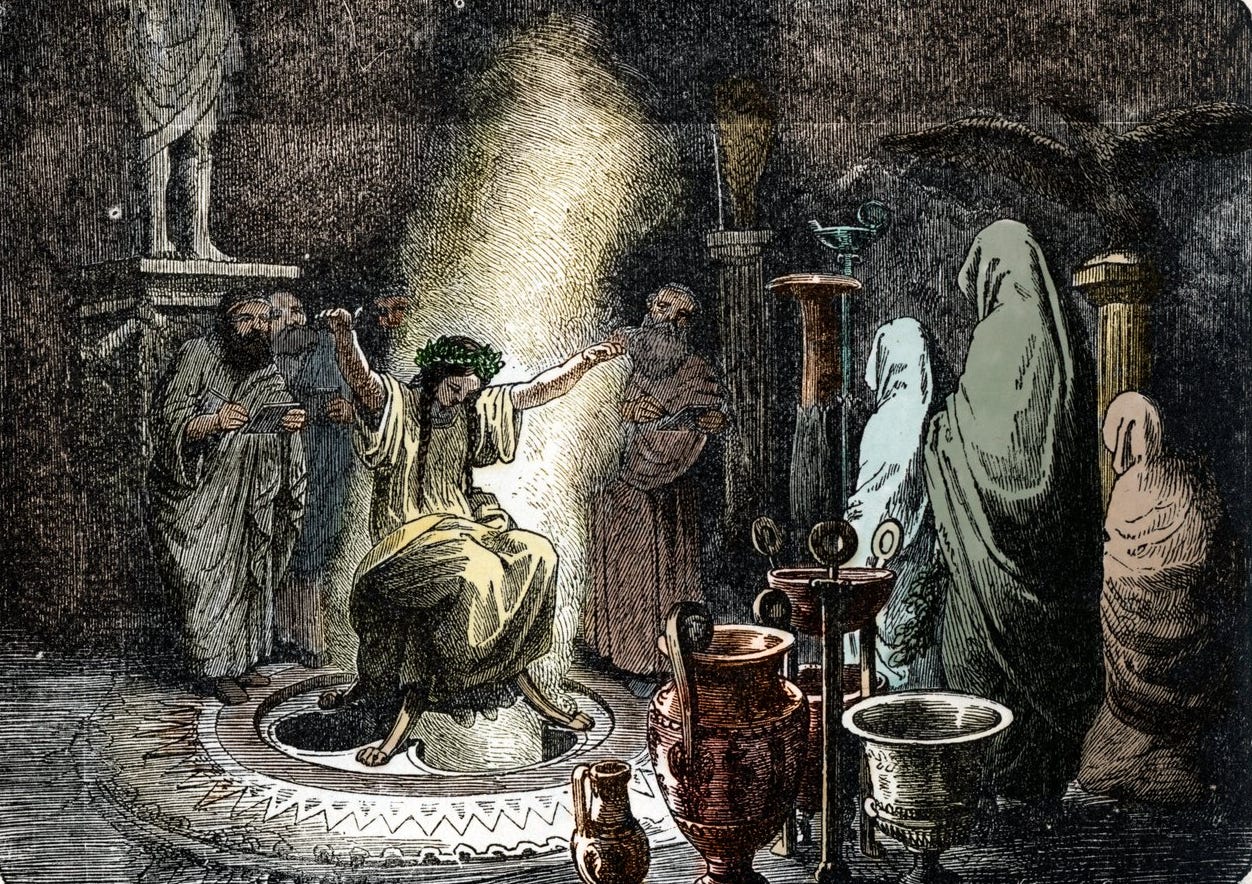

From another one of Aristeas’ 7th century BC contemporaries, Alcaeus, we find the ‘Hymn to Apollo,’ which speaks of the solar god, Apollo, disobeying the wishes of his father, Zeus, and flying to the land of Hyperborea on his chariot, which was pulled by swans:

“When Apollo was born, Zeus furnished him forth with a golden headband and a lyre, and giving him moreover a chariot to drive — and they were swans that drew it — , would have him go to Delphi and the spring of Castaly, thence to deliver justice and right in oracles to Greece. Nevertheless once he was mounted in the chariot, Apollo bade his swans fly to the land of the Hyperboreans.”

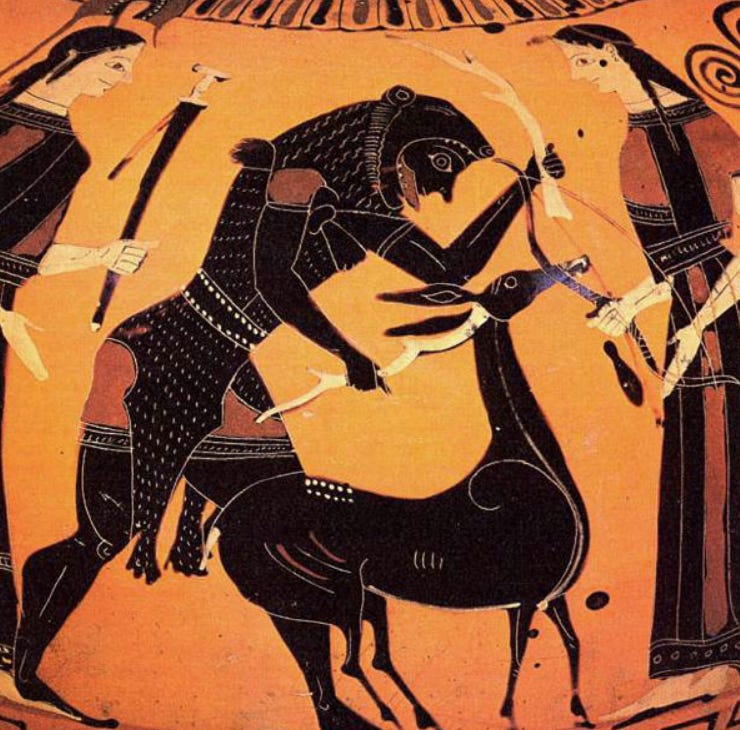

Echoing this idea that the Hyperboreans had some relation to Apollo, the 6th century BC Greek poet, Pindar, wrote that the Hyperborean people were the “servants of Apollo,” and that they would sacrifice donkeys and sing praises in their worship of the solar god. In a slightly less direct way, Pindar also mentions that Hercules traveled to Hyperborea during his third labor, in search of the Caryneian Hind; a deer with golden horns:

“The fate that bound the sire and son urged him on the quest of the doe with the golden horns… On his quest of that doe had he seen the far-off land, beyond the cold blast of Boreas; and there had he stood and marveled at the trees, and had been seized with sweet desire for them.”

Following Pindar was Herodotus, of the 5th century BC, who is considered to be the Father of History and who is, perhaps, one of the most referenced ancient Greek writers. Herodotus wrote extensively about what he read in the ‘Arimaspea,’ making him one of the most bountiful sources of Hyperborean information, which has ultimately given us our first clear geographic description of where Hyperborea would have been located:

“Aristeas however the son of Caystrobios, a man of Proconnesos, said in the verses which he composed, that he came to the land of the Issedonians being possessed by Phoebus [Apollo], and that beyond the Issedonians dwelt Arimaspians, a one-eyed race, and beyond these the gold-guarding griffins, and beyond them the Hyperboreans extending as far as the sea: and all these except the Hyperboreans, beginning with the Arimaspians, were continually making war on their neighbours, and the Issedonians were gradually driven out of their country by the Arimaspians and the Scythians by the Issedonians, and so the Kimmerians, who dwelt on the Southern Sea, being pressed by the Scythians left their land.”

Some of these groups mentioned by Herodotus are well-known and well-documented by modern historians; the Kimmerians are known to have lived on the east side of the Black Sea, just north of what is now Georgia, while the Scythians are known to have lived in eastern Europe and western Russia. From this, we can continue north and east, further away from Greece, where we would find the Issedones, then the Arimaspians, then the Griffins, then, finally, the Hyperboreans, whose land stretches to the sea.

Herodotus also mentions that the Hyperboreans would regularly send gift-bearing maidens to the Temple of Apollo at Delos in Greece; passing through all the aforementioned lands:

“The maidens, I say, have this honour paid them by the dwellers in Delos: and the same people say that Arge and Opis also, being maidens, came to Delos, passing from the Hyperboreans by the same nations which have been mentioned, even before Hyperoche and Laodike.”

Everything Herodotus knew about the Hyperboreans, Herodotus learned by living amongst his ancient Greek contemporaries, and by reading the available Greek literature, from many of the writers we’ve previously mentioned. That being said, it cannot be denied that Herodotus was somewhat skeptical regarding the existence of Hyperborea. From Herodotus’ point of view, if there are, in fact, people living beyond the north wind, Hyperboreans, that there must also be people living beyond the south wind; Hypernotians:

“If however there are any Hyperboreans, it follows that there are also Hypernotians; and I laugh when I see that, though many before this have drawn maps of the Earth, yet no one has set the matter forth in an intelligent way.”

In the time in which Herodotus lived, the possibility of human civilization existing below the northern African coast seemed impossible; this being the south wind, Hypernotian area. As such, it is this concept that makes him skeptical of human civilization existing in the northern, Hyperborean region. Given what we know today, this idea might seem intellectually shallow and dismissive, but it is worth noting that the common thought amongst the Greeks at this point in time was that Greece, specifically Delphi, was the ‘Omphalos’ of the world; Omphalos meaning the navel, or center. Through this lens, we can begin to understand how radical the Hyperborean concept may have sounded to some ancient Greeks.

One of Herodotus’ 5th century BC contemporaries, Hippocrates, would have also had access to the writings of Aristeas, and it is from him that we learn that the Scythians, among other things, live beneath the Riphean Mountains:

"In respect of the seasons and figure of body, the Scythian race, like the Egyptian, have a uniformity of resemblance, different from all other nations; they are by no means prolific, and the wild beasts which are indigenous there are small in size and few in number, for the country lies under the Northern Bears [Arctos], and the Rhiphaean mountains, whence the north wind blows; the sun comes very near to them only when in the summer solstice, and warms them but for a short period, and not strongly."

On this topic, we can look to another Greek writer of the 5th century BC, Hellanicus. Like Herodotus and Hippocrates, Hellanicus would have had access to the writings of Aristeas, but much like Aristeas’ own writings, much of Hellanicus’ work has been lost. That being said, in the 2nd century AD, from the highly respected early-Christian theologian, Clement of Alexandria, we find a direct reference to a description written by Hellanicus in which he details the location of Hyperborea:

“And the Hyperboreans, Hellanicus relates, dwelt beyond the Riphean mountains.”

One of Hellanicus’ pupils, Damastes, relayed similar information about the location of the Hyperboreans:

"The Issedones live beyond the Scythians and the Arimaspoi beyond them, and beyond the Arimaspoi there are the Rhipaian mountains, from which the wind of Boreas blows; and snow never abandons them. Beyond these mountains live the Hyperboreoi, until the other sea."

It is unclear whether or not Damastes had access to ‘Arimaspea’ or if he was relaying information given by Herodotus, Hippocrates, or Hellanicus, but regardless, the information is consistent with everything else we know about Hyperborea’s location; Hyperborea exists beyond the Riphean Mountains.

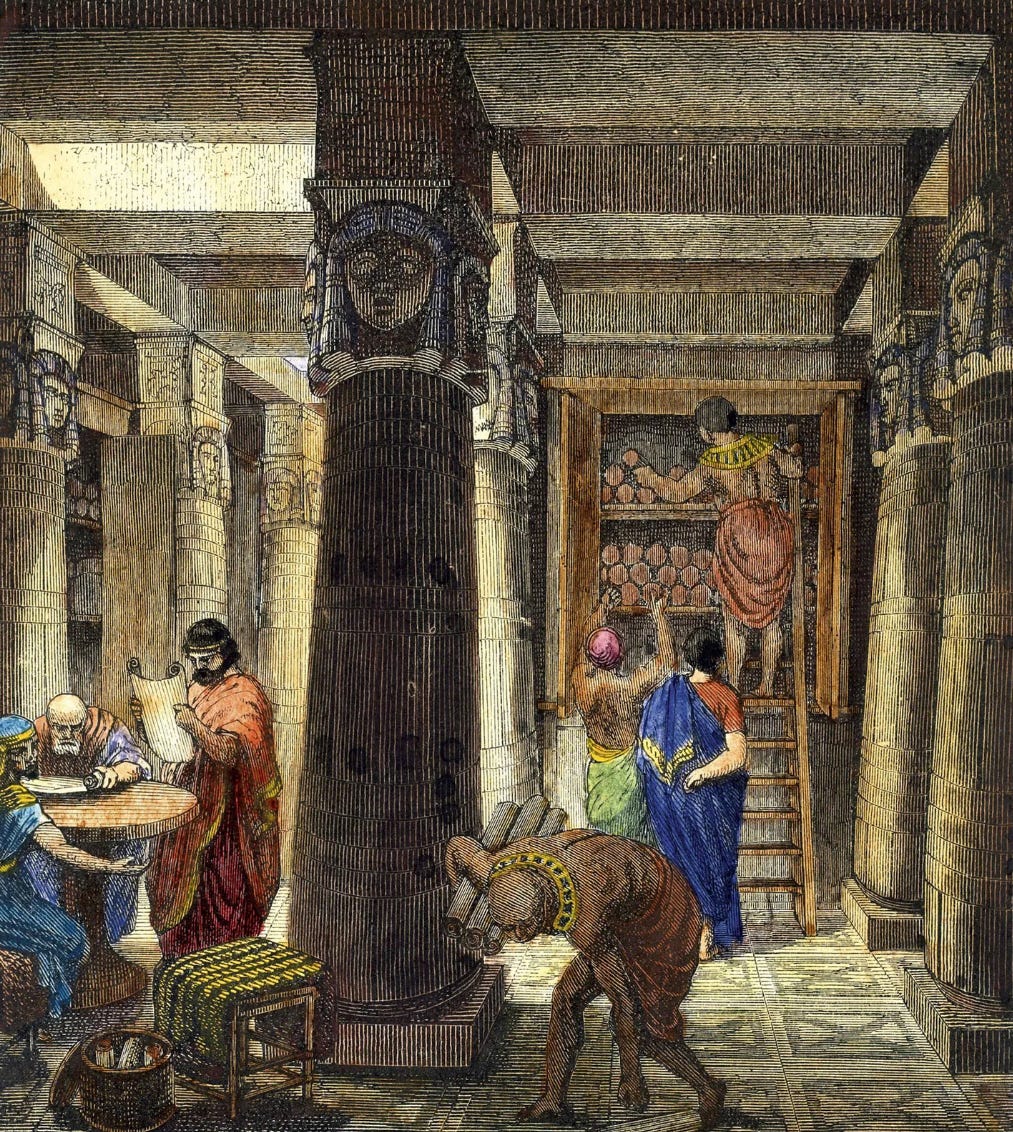

In the 3rd century BC, we find Callimachus, a Greek author who worked in the Library of Alexandria, relaying more information about the Hyperboreans and their customs, speaking of the Hyperborean maidens that Herodotus spoke of:

“The sons of the Hyperboreans send them away from the Rhipaean mountain, where rich 10 sacrifices of asses most please Phoebus [Apollo].”

At this point in history, Hyperborean worship of the solar god Apollo and the ceremonial sacrifice of donkeys had been established and reiterated by numerous ancient Greek writers. One of Callimachus’ pupils, Eratosthenes, who ultimately became head of the Library of Alexandria, is written about by Strabo, a Greek writer of the 1st century AD, who relayed one of Eratosthenes’ critiques of Herodotus regarding Hyperborea:

“Herodotus having observed that there could be no such people as Hyperborean, inasmuch as there were no Hypernotii, Eratosthenes calls this argument ridiculous, and compares it to sophism.”

What can be determined from the writings of Callimachus and Eratosthenes, and their presence at the Library of Alexandria in the 3rd century BC, is that an abundance of literature pertaining to Hyperborea must have been stored within the library, but ultimately lost during the burning of the library in the 1st century AD.

Similar to Pindar’s 6th century BC assertion that Hercules traveled to Hyperborea in search of the Caryneian Hind, Apollodorus of the 2nd century BC writes that Hercules traveled to Hyperborea for his eleventh labor; in search of the golden apples of the Hesperides:

“Eurystheus ordered Hercules, as an eleventh labour, to fetch golden apples from the Hesperides, for he did not acknowledge the labour of the cattle of Augeas nor that of the hydra. These apples were not, as some have said, in Libya, but on Atlas among the Hyperboreans.”

Perhaps one of the last great writers of the ancient world to have access to the full catalog of the Library of Alexandria was Pliny the Elder, a Roman man of the 1st century AD who is considered to be the Father of Encyclopedias, making it his life’s endeavor to gather the world’s information into one, concise piece of literature. Pliny wrote extensively of Hyperborea, describing the geographic area in which Hyperborea was located:

“From the extreme north northeast to the point where the sun rises in the summer, it is the country of the Scythians. Still further than them, and beyond the point where north north-east begins, some writers have placed the Hyperborei, who are said, indeed, by the majority to be a people of Europe.”

Pliny not only describes the geographic location of Hyperborea, but also the abnormal astronomical conditions in Hyperborea:

“Behind these mountains, and beyond the region of the northern winds, there dwells, if we choose to believe it, a happy race, known as the Hyperborei, a race that lives to an extreme old age, and which has been the subject of many marvellous stories. At this spot are supposed to be the hinges upon which the world revolves, and the extreme limits of the revolutions of the stars.”

Pliny’s writing is representative of the ever-increasing knowledge that the ancient academics had of the world. Just 500 years prior, as seen with Herodotus, the common belief was that Greece was the center of the world, whereas Pliny properly describes the astronomical activity of the polar region, the axis on which the earth rotates. Although these descriptions of the far north are astronomically correct, this is perhaps the first time we hear them from an ancient Greek or Roman writer. As such, we can be certain that by Pliny’s time, other men than Aristeas have traveled to Hyperborea and returned with their findings. In fact, Pliny speaks to this notion by insisting that the proof for Hyperborea is beyond any reasonable doubt:

“Nor are we at liberty to entertain any doubts as to the existence of this race [the Hyperboreans]; so many authors are there who assert that they were in the habit of sending their first-fruits to Delos to present them to Apollo, whom in especial they worship.”

From Pliny’s 1st century AD contemporary, Plutarch, we hear of yet another interesting reference to the Hyperboreans. Plutarch was a Greek historian, philosopher, and sanctuary priest at the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, which was in a state of slight disrepair by Plutarch’s time. As such, Plutarch made it his goal to revitalize the shrine, writing:

“The priest from the Hyperboreans, with courts and flutes and harps, will be sent to Delphi as of old.”

Curiously, we hear something similar from the 2nd century Roman Author named Aelian, who similarly detailed the Hyperborean’s affinity for music:

“Now whenever the singers sing their hymns to the god [Apollo] and the harpers accompany the chorus with their harmonious music, thereupon the swans also with one accord join in the chant and never once do they sing a discordant note or out of tune, but as though they had been given the key by the conductor they chant in unison with the natives who are skilled in the sacred melodies.”

In the 2nd century AD we find the writings of Greek geographer, Pausanias, who further details Haracles’ interactions with the Hyperboreans; suggesting that the golden apples of the Hesperides were actually Hyperborean olives:

“Heracles, being the eldest, matched his brothers, as a game, in a running-race, and crowned the winner with a branch of wild olive, of which they had such a copious supply that they slept on heaps of its leaves while still green. It is said to have been introduced into Greece by Heracles from the land of the Hyperboreans, men living beyond the home of the North Wind.”

Pausanias also relays information about the creation of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, writing that the Hyperboreans were heavily involved in the construction of the temple, which was home to the legendary Oracle of Delphi; perhaps the most influential oracle in all of ancient Greece.

In the 3rd century AD we find the extensive writings from the neoplatonic philosophers Porphyry and Iamblichus, who are just as known for their documentation of ancient Greek history as they are for their philosophy. Porphyry and Iamblichus both authored biographies on Pythagoras, who, very interestingly, has a long and detailed relationship with Hyperborea; a relationship that we will unpackage at a later point.

As you can see, from the ancient Greco-Roman world we find an immeasurable amount of information about the Hyperboreans. Now, having established a foundational understanding of the Hyperborean concept as it manifested amongst a plurality of ancient writers, we might begin to focus on various aspects of Hyperborea with a higher degree of detail and granularity. What may come as a surprise to the reader, our difficulty moving forward is not for lack of Hyperborean matter to discuss, but rather, finding the proper way to navigate through the overwhelming amount of Hyperborean matter that we do have.

Imagine slaying the Hydra and coming up with hydraulic engineering to clean cow dung from some stables just to return and be told "Nuh huh, doesn’t count. Bring me an apple from the literal end of the globe"