The 'Hyperborean Apollo'

Pythagoras is a name that will very likely sound familiar to the reader as a consequence of his famous geometric equation, the ‘Pythagorean Theorem.’ That being said, something that is both well-documented and little-discussed is that Pythagoras was viewed by his followers to be the ‘Hyperborean Apollo;’ that is, the human incarnation of the Hyperborean sun god. It is known that Pythagoras lived between 570 BC and 495 BC, but what is much less often discussed is that Pythagoras was much more than a mathematician; he was also a revolutionary theologian and philosopher, ultimately creating his own philosophical school after having spent several decades studying alongside priests in Egypt and Magi in Persia.

The followers of Pythagoras’ school of philosophy were known as Pythagoreans, all of whom rigidly followed Pythagoras’ teachings and viewed him as the human manifestation of the Hyperborean Apollo. The association between Pythagoras and the Hyperborean sun god is widely documented by ancient writers and must have been well-known information at the time. From the Roman author Aelian, in the 2nd century AD, we hear that Aristotle, in the 4th century BC, wrote of Pythagoras’ relation to the Hyperborean Apollo:

“Aristotle says that Pythagoras was called by the people of Croton the Hyperborean Apollo.”

Shortly after the time of Aelian, in the 3rd century AD, the Roman biographer of Greek philosophers, Diogenes Laertius, corroborated and added to Aelian’s writings on Pythagoras, also referencing the writings of Aristotle:

"Pythagoras is said to have been a man of the most dignified appearance, and his disciples adopted an opinion respecting him, that he was Apollo who had come from the Hyperboreans."

“The only altar at which he worshiped was that of Apollo the Father, at Delos, which is at the back of the altar of Ceratinus, because wheat, and barley, and cheesecakes are the only offerings laid upon it, being not dressed by fire; and no victim is ever slain there, as Aristotle tells us in his Constitution of the Delians.”

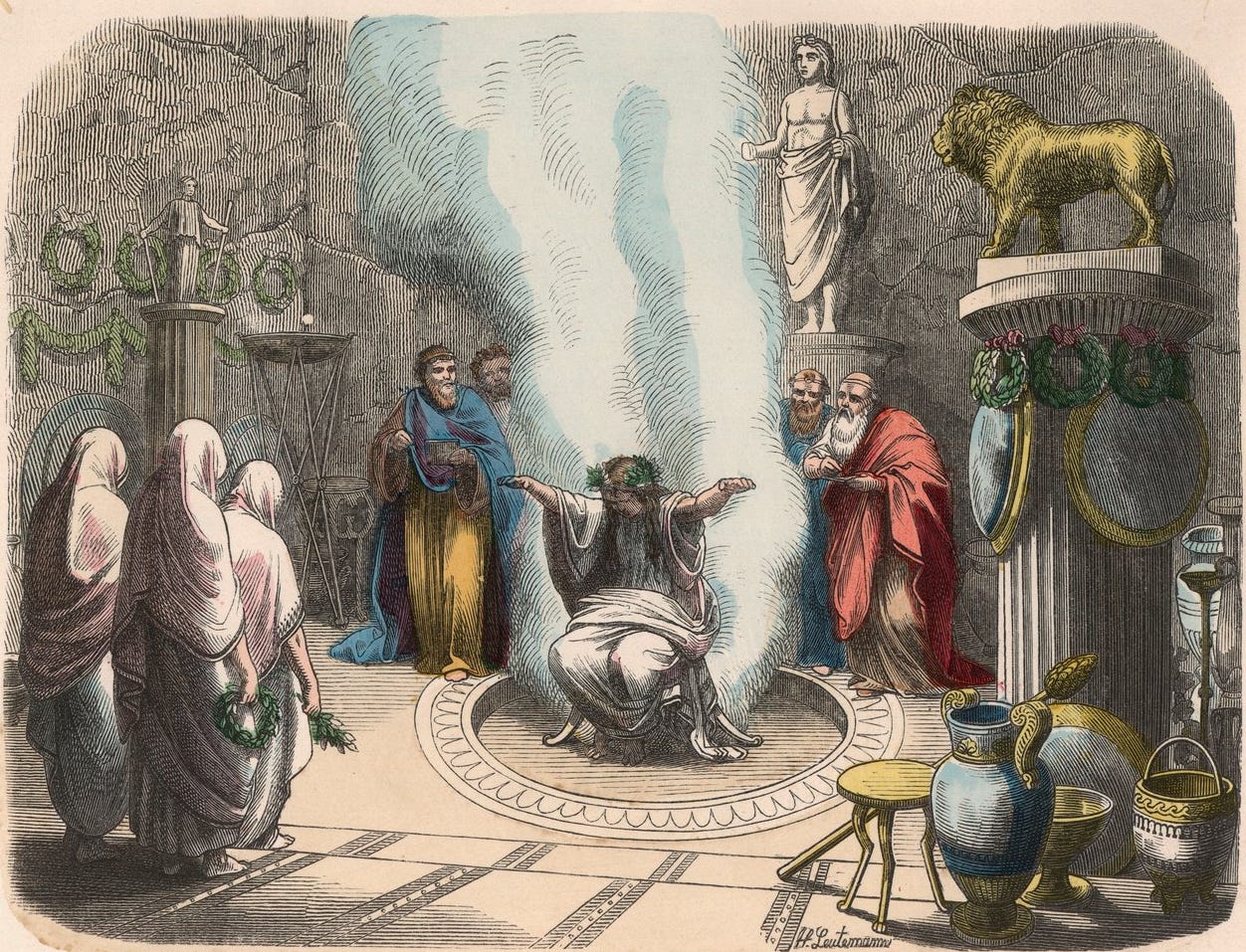

In addition to his incredible philosophical contributions, Aristotle is known to have written or co-authored numerous legislative constitutions for the Greek states of his time. Regrettably, only his Athenian Constitution has survived to modern day, meaning that his aforementioned Delian Constitution has been lost to the ages, but we find reference to its contents, nonetheless. From Diogenes Laertius’ 3rd century AD contemporary, the Tyrian philosopher by the name of Porphyry, we find what is perhaps the ancient world’s most detailed surviving biography of Pythagoras, titled the ‘The Life of Pythagoras.’ In this biography, Porphyry introduces what is perhaps one of the most curious and interesting pieces of information regarding Pythagoras’ relation to the Hyperborean Apollo; that he met and interacted with the previously mentioned Hyperborean priest, Abaris. Porphyry writes:

“It is well known that Pythagoras showed his golden thigh to Abaris the Hyperborean, to confirm him in the opinion that he was the Hyperborean Apollo, whose priest Abaris was.”

For the ancient Greeks, the “thigh” in this context was not a literal body part, but rather an idiom that referenced paternal lineage, most directly translating to the English phrase “begotten to.” So in this case, Porphyry is relaying that Pythagoras, through some means, proved his paternal lineage to Abaris convincingly enough that Abaris acknowledged him as the Hyperborean Apollo.

Regarding this initial interaction between Pythagoras and Abaris, Porphyry’s student, Iamblichus, writes:

“Then Pythagoras described to him several details of his sanctuary, as proof of deserving being considered divine. Pythagoras also added that he came (into the regions of mortality) to remedy and improve the condition of the human race, having assumed human form lest men disturbed by the novelty of his transcendency should avoid the discipline he advised. He advised Abaris to stay with him, to aid him in correcting (the manners and morals) of those they might meet…”

Based on the writings of Iamblichus, it would seem that Pythagoras was able to convince Abaris of his Apollonian divinity by sharing with him information that he otherwise couldn’t have known. To corroborate this notion of divinity, we turn to the writings of the 3rd century BC Greek mathematician Apollonius, who spoke of Pythagoras’ paternal lineage:

"Pythais, of all Samians the most fair; Jove-loved Pythagoras to Phoebus [Apollo] bare!"

As seen, Pythagoras’ mother’s name was Pythais; the two names bearing some resemblance. Interestingly, the names of Pythagoras and his mother Pythais don’t just bear a striking resemblance out of coincidence, but rather, they stem from a common etymological origin. In ancient Greece, the ‘Pythia’ was the high priestess of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, serving as its oracle and otherwise being known as the ‘Oracle of Delphi.’ It is from this root-word, ‘Pythia,’ that the names of both Pythagoras and his mother Pythais originate, with the second half of Pythagoras’ name, ‘Agora,’ meaning ‘assembly’ or ‘gathering place.’ As such, it can be understood that Pythagoras’ name most directly translates to ‘place of Apollo worship,’ which is an interesting congruence with the ancient belief that he was the human incarnation of the Hyperborean Apollo.