The Hyperborean Priest

A name that has yet to be mentioned is that of “Abaris the Hyperborean,” who we first hear of from Plato and Herodotus in the 5th century BC, both of whom say that Abaris was a traveling Hyperborean priest of Apollo, known for his ability to cure sickness and remedy the ill.

However, it is from the 2nd century AD Greek writer, Harpokration, that we are given information about Abaris that is more substantive:

“When a plague, they say, had arisen throughout the whole inhabited world, Apollo responded to both Greeks and barbarians, when they asked, that the Athenian people was to make prayers on behalf of all. And when many nations were sending embassies to them, they say that Abaris also came, an ambassador from the Hyperboreans. The time in which he was present is disputed. For Hippostratos says that he was present in the 53rd Olympiad, while Pindar (says that it was) in the time of Kroisos, king of the Lydians, and others (that it was) in the 21st Olympiad.”

From Harpokration, we hear three possible timeframes in which Abaris the Hyperborean may have visited Greece:

According to Hippostratus of the 1st century BC, Abaris came to Greece during the 53rd Olympiad, which took place 568 BC.

According to Pindar of the 6th century BC, Abaris came to Greece during the reign of Kroisos, King of the Lydians, who reigned from 585 BC to 546 BC.

According to other anonymous sources, Abaris came to Greece during the 21st Olympiad, which took place in 696 BC.

Worth noting, the first two time frames overlap and are from named sources, Hippostratus and Pindar, whereas the third time frame comes to us anonymously, and significantly deviates from the other two time frames. As such, the first two time frames given seem much more plausible, but what do we know of Kroisos, King of the Lydians, who was said to reign during this time? Interestingly, Kroisos is known for his reverence of Apollo, sending countless offerings to the Temple of Apollo at Delphi during his reign, and funding the construction of a golden statue of Apollo for the Spartans. In fact, it is in the legend of Kroisos that we find a pertinent reference worth making note of. Bacchylides, Greek historian of the 5th century BC, writes that after Kroisos’ army had been defeated by the Persian armies of Cyrus the Great, rather than capture and enslavement, Kroisos sought suicide for his family and for himself:

“Croesus was protected by the god of the golden lyre, Apollo. When he had come to that unexpected day, Croesus had no intention of waiting any longer for the tears of slavery. He had a pyre built before his bronze-walled courtyard, and he mounted the pyre with his dear wife and his daughters with beautiful hair; they were weeping inconsolably. He raised his arms to the steep sky and shouted, "overweening deity, where is the gratitude of the gods? Where is lord Apollo?”

“But when the flashing force of terrible fire began to shoot through the wood, Zeus set a dark rain-cloud over it, and began to quench the golden flame. Nothing is unbelievable which is brought about by the gods' ambition. Then Apollo, born on Delos, brought the old man to live among the Hyperboreans.”

Given that Abaris disappeared from Greece in the approximate timeframe that Kroisos is said to have been saved by Apollo and led to Hyperborea, it is speculated that it was none other than Abaris that brought the king to Hyperborea as a reward for his faithful service to Apollo.

Regarding the ancient description of Abaris, we might turn to the 3rd century AD writings of Iamblichus:

“This Hyperborean Abaris was elderly, and most wise in sacred concerns, being a priest of the Apollo there worshipped.”

Something that we have yet to mention, and something that modern historians have yet to reconcile or explain, is the incredibly fascinating and provocative description of Abaris’ “arrow.” Herodotus writes:

“Let this suffice which has been said of the Hyperboreans; for the tale of Abaris, who is reported to have been a Hyperborean, I do not tell, namely how he carried the arrow about all over the earth…”

Now, as a Hyperborean priest of Apollo, carrying an arrow, which is often associated with Apollo, wouldn’t seem out of the ordinary when looked at through the mythological lens. That said, something that can’t be ignored as it relates to Abaris’ “arrow” is it’s navigational properties. Iamblichus writes:

“From this Abaris Pythagoras took the golden arrow without which he could not find his way, and so made Abaris witness to his power.”

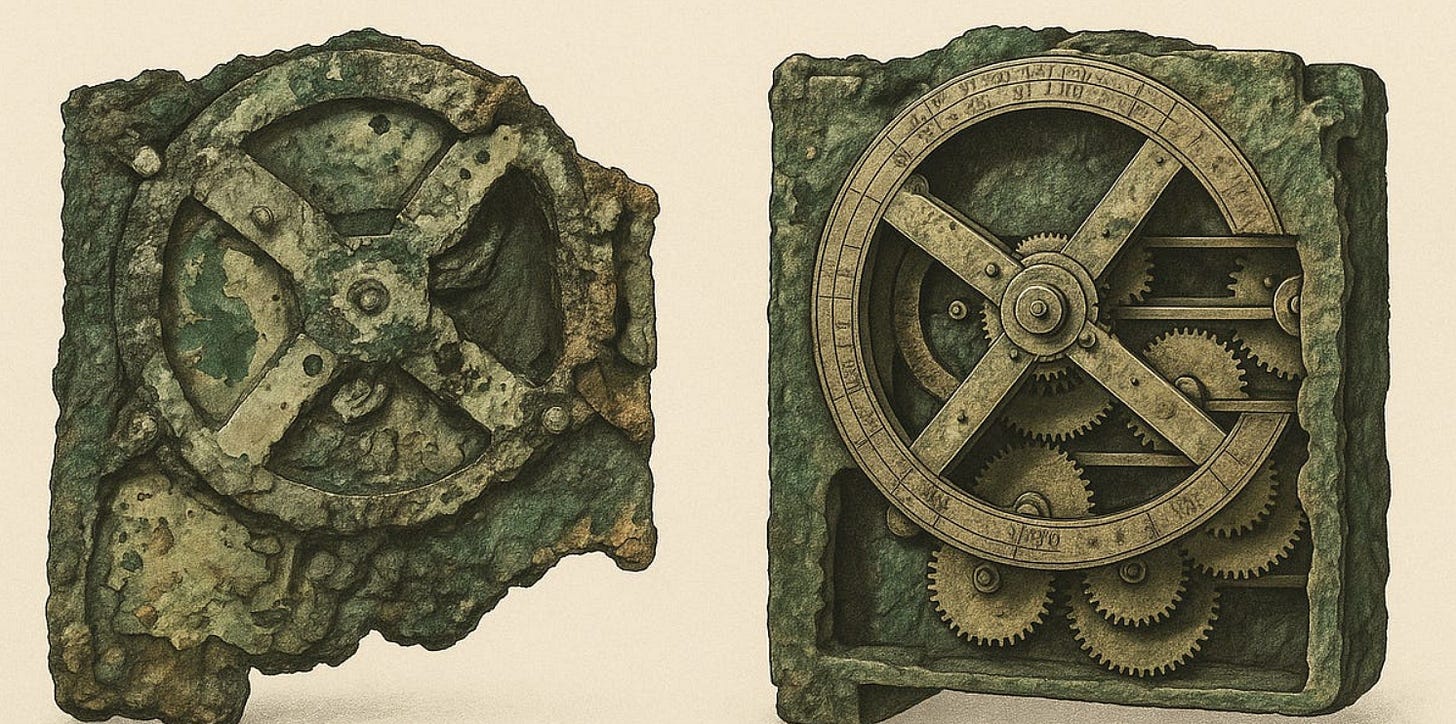

Of course, when looked at through a modern lense, it’s difficult not to imagine that Abaris’ arrow was a navigational compass. Problematically, the navigational compass wasn’t first used for another 1,500 years after the time of Abaris, with modern historians giving credit to the Chinese of the Song Dynasty in 1,040 AD.

In a very clear and direct way, it is said that without his “arrow,” Abaris is unable to find his way. Worth noting, Iamblichus wrote this passage, based on much older referential works, approximately 700 years before the supposed Chinese invention of the navigational compass. Is it possible that the navigational compass was invented and used by the Hyperboreans as far back as the time of Abaris in the 5th century BC? Given what we now know about the ancient Greek’s Antikythera Mechanism, perhaps nothing is off the table.